Effects of COVID-19 on Physics Undergraduate Education and Career Preparation

Fall

2021

Feature

Effects of COVID-19 on Physics Undergraduate Education and Career Preparation

The new landscape and recommendations for going forward

By:Brad R. Conrad, Director of SPS and ΣΠΣ; Rachel Ivie, Senior Research Fellow, American Institute of Physics (AIP); Patrick Mulvey, Research Manager, AIP Statistical Research Center; and Starr Nicholson, Senior Research Analyst, AIP Statistical Research Ce

The pandemic has left no aspect of higher education unaltered. To best serve undergraduate physics majors, we need to expect and plan for changes in the trends in physics higher education and careers. Before the pandemic, long-term shifts in higher education were well underway, including changes to general undergraduate enrollment trends, college education costs, and the backgrounds of the students entering our programs. The pandemic caused immediate and dynamic modifications from what was expected by educators, including additional shifts to total enrollment, shifts in student demographics, and the pertinence of the support structures available to current and incoming students. As classrooms approach their new normal this fall, providing the best education requires being cognizant of these shifts and the educational reality current undergraduate students have experienced for the last year and a half.

Overall trends before COVID-19

From 1999 through the 2020 academic year, the overall number of undergraduates graduating with a physics degree from a US institution has steadily increased.1 Over roughly the same period of time, the percentages of degrees earned by women2 and African Americans3 have stayed roughly flat or even decreased, which is evidence of a systemic problem.

More broadly, while the total number of undergraduates in college rose through about 2010, enrollments have been largely flat since then, with a relatively large decrease expected based on population demographics between now and the end of the current decade. Some models predict, based on the current population demographics, that enrollment changes will not be uniform across institution type. While elite institutions (top 50 ranking) could expect flat enrollments over the next decade, nationally recognized (rankings of 50–100 nationally) and to a larger degree, regular institutions (ranked 101 and higher) could expect large decreases in the number of students who enroll. Correspondingly, as national population trends differ by region, it’s to be expected that the impact to departments could be both regional and type specific.4

Shifts due to the pandemic

The pandemic caused new challenges and shifts for colleges and universities. Between fall 2019 and fall 2020, there was a total student enrollment decrease of 2.5%. The shifts were not uniform: undergraduate enrollment fell 3.6%, with first-year student enrollment falling 13.1%. The impact on public two-year colleges has also been marked. Overall, two-year college enrollments decreased 10%.5 Based on national data, we also know that the observed decrease in first-time enrollment is not due to a decrease in high school graduation rates.

There are reported differences in enrollment demographics as well. While enrollment for women is down by less than 1%, enrollment for men is down 5.1%.4 Fewer low-income students and students from urban settings are enrolling.6

Although this enrollment data was not broken down by intended major or at the department level, we should not assume that physics has been unaffected. Rather, keeping these observations in mind at the department planning level is imperative if undergraduate programs are to be responsive to the changing needs of incoming students. As physics and astronomy departments aim to support students who are traditionally underrepresented in physics or who may not feel connected to a department’s culture, they must be aware that these students may be even more isolated going forward. In short, incoming students this fall will have a different aggregate profile and may need different resources and support networks to excel.

The physics and astronomy student experience

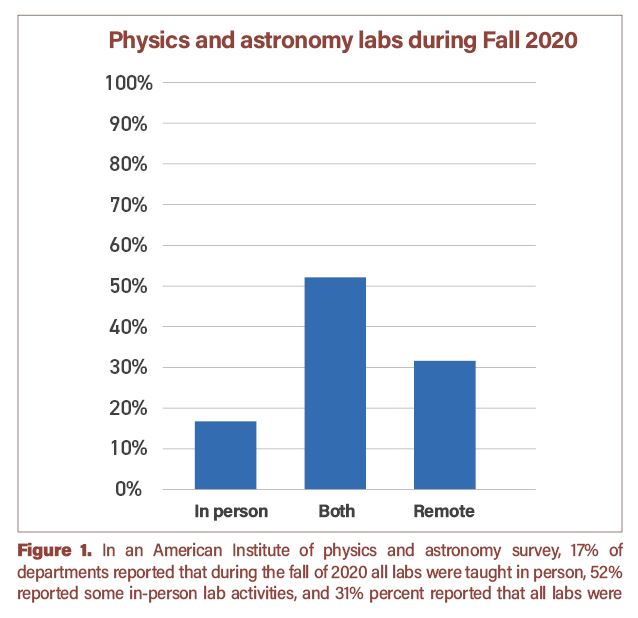

While some of the effects due to COVID-19 are likely to dissipate, namely, the lack of availability of in-person courses and experiences, the ramifications of being virtual (or hybrid) for an extended period of time will have long-lasting effects in terms of building career skills and fostering student belonging. Experimental course sequences, often built around hands-on skills, public speaking, and group work, had to be substantially modified in many physics and astronomy departments. In a 2020–21 survey by the American Institute of Physics, 31% percent of departments report that all lab courses were taught virtually, while an additional 52% report that only some in-person activities took place (Fig. 1). In another AIP survey of 2021 college seniors who are physics and astronomy majors, 72% reported that they believed they learned less as a result of classes being switched from in person to online.

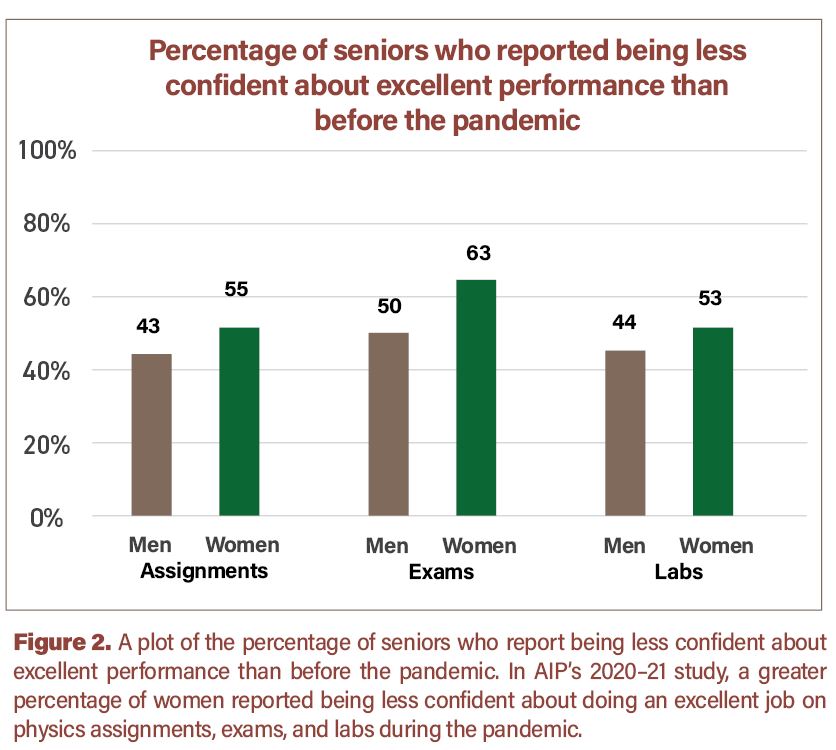

Departments should also consider the fact that the pandemic had different effects on different types of students. For example, research has shown that COVID-19 negatively affected women in STEMM fields in multiple ways.7 AIP’s study of senior physics and astronomy majors also shows gender differences in the experiences of women and men as a result of COVID-19. Compared to men, a statistically significant greater percentage of women reported being less confident about doing an excellent job on physics assignments, exams, and labs during the pandemic (Fig. 2).8

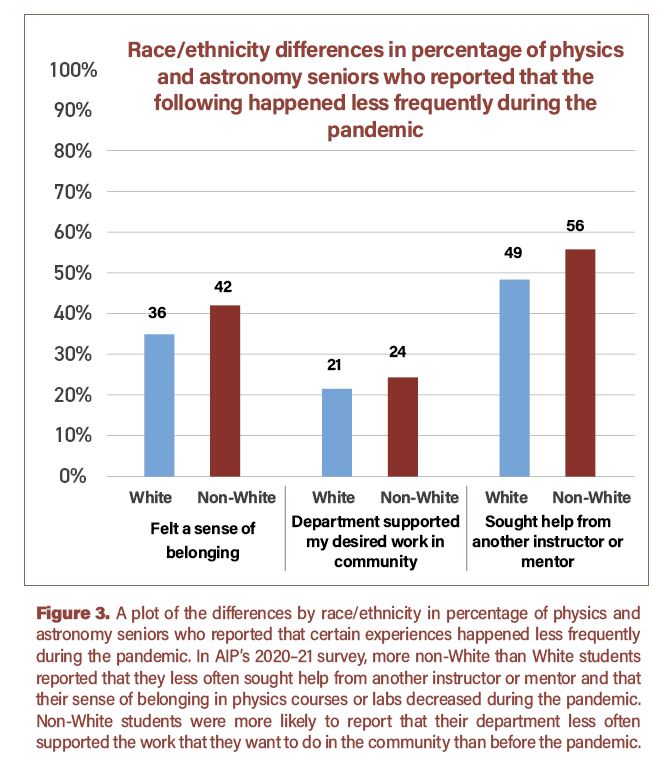

AIP’s TEAM-UP report,9 the result of a task force study focused on increasing the number of African American students earning bachelor’s degrees in physics and astronomy, found that one key factor in the persistence and success of African American students is a sense of belonging to the physics community. In AIP’s survey of senior physics and astronomy majors, significantly more non-White than White students reported that their sense of belonging in physics courses or labs decreased during the pandemic (Fig. 3). No student of any race or ethnicity should feel that they do not belong, but the greater likelihood of non-White students to have this experience is especially troubling. Departments should pay special attention to this and consult the TEAM-UP report for recommendations.

Furthermore, the TEAM-UP report notes that various types of support, including academic and financial, are essential for the persistence and success of African American students. However, in the AIP survey of physics and astronomy seniors, 42% of non-White students said that they were in a worse place financially than before the pandemic, compared to 36% of White students. The pandemic also disproportionately affected non-US students; more than 50% of these students said they were financially worse off than before the pandemic.

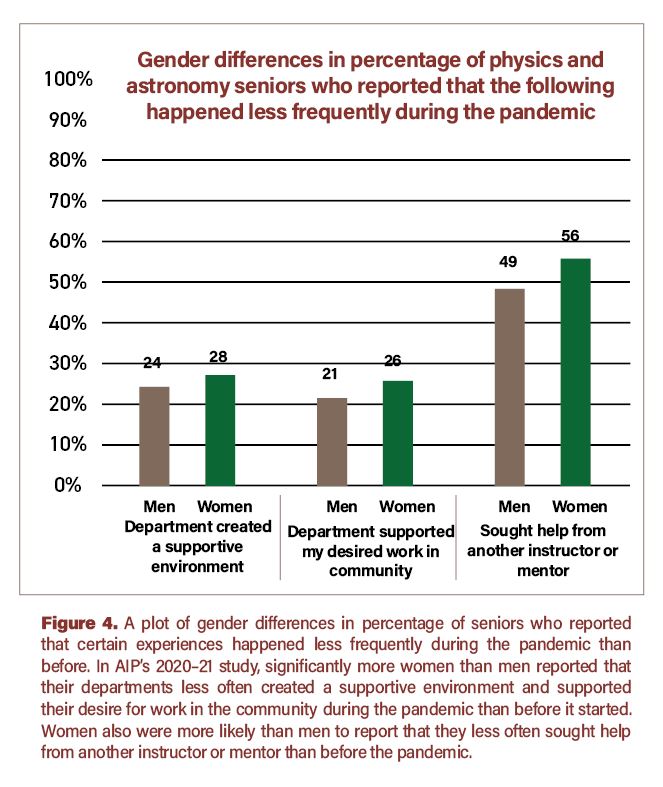

Other types of support are important for student success. The TEAM-UP study found that for African American students, a sense of connection between physics and “activities that improve society or benefit [the] community” is essential. Therefore, departments should make efforts to support this connection. However, AIP’s study of senior physics and astronomy majors found that significantly more non-White than White students reported decreased departmental support for “the work that I want to do in my community” as a result of the pandemic (Fig. 3). There was also a significant gender difference in this perception, with more women than men saying departmental support for desired community work decreased. Furthermore, significantly more women than men reported that their departments created a supportive environment less often during the pandemic than before it started (Fig. 4).

Findings from AIP’s Statistical Research Center show that new physics bachelors who are employed in the private sector report solving technical problems, working on a team, performing quality control, design and development, and using specialized equipment as being some of the most regularly used workplace skills10—all of which are honed by experimental courses, group work, and laboratory experiments. Students’ access to peer groups has been limited during the pandemic: 54% percent of senior physics and astronomy majors said they never or rarely had access to in-person or online study groups with peers. Although not part of the survey data, we also know that students have had limited access to research conferences, have not been able to present their work in person, and have not been able to network as easily with other students and physicists who are not connected to the courses they are taking. The AIP senior survey found that higher percentages of women (compared to men) and students who are non-White (compared to White students) report that they less often sought help from another instructor or mentor than they did before the pandemic (Figs. 3 and 4).

Perhaps because of the lack of opportunity to network, senior physics and astronomy majors reported that compared to before the COVID pandemic, they felt less confident that they could get full-time employment in their chosen field (52% of respondents) and less confident that they could get accepted to a graduate program in physics or another STEM field (47% of respondents). While confidence in getting a full-time job could be the result of concern about economic changes due to the pandemic, the lower confidence in being accepted to graduate school could be related to students’ perceptions that they learned less during remote classes and labs.

In summary, the fall 2021 semester has a vastly different landscape. Enrollments are down, particularly for the types of students who may need additional support. Returning students report that they learned less during the pandemic, were faced with fewer opportunities to connect with other students and faculty members, and have concerns about getting a job or being accepted into graduate school. Some of the pandemic effects were greater for students from underrepresented groups, who report a reduced sense of belonging, less confidence in their ability to succeed in school, and being in a worse place financially.

Areas of consideration

As a result of these changes, we offer some areas for consideration by undergraduate departments:

- The changing demographics of those entering their programs: How can we support students at risk of being isolated or who feel like they don’t belong? How might we adjust our recruiting efforts in light of the new enrollment landscape?

- Equipping students with a well-rounded skill set: How do we adjust courses and extracurricular offerings, and help students develop skills that were missed because of the pandemic?

- Supporting vibrant undergraduate groups and student leadership: How can faculty engage with and support a sense of student community? How can we help second-year students fully engage in the community after their nontraditional first year? How do we encourage students to form study groups and seek academic assistance from faculty after a year of isolation? Does the department build strong connections to our undergraduate student leaders? How are we connecting students to community or university resources that will support them as people and researchers?

- The unequal impact of COVID-19 on different groups of students: How can the department increase student belonging and foster success for women and students from other minoritized groups? How can we help students under heavy financial burdens feel that they belong in physics and continue their physics education?

- Student preparation for the workforce and graduate school: How can we help students build confidence in their knowledge, skills, and abilities? How can we set them up for success in job seeking and applying to graduate programs? How can we equip them to discuss the impact of COVID-19 on their education in productive ways with potential employers and graduate departments?

- Support undergraduate research: How can we increase hands-on research opportunities for students who weren’t able to participate during the pandemic, or who had to switch to computational or theoretical research projects? How can we help students who weren’t able to participate in hands-on research projects learn about research careers?

Awareness of changing enrollment trends, demographics, and student experiences should lead departments to make changes that respond to these findings and further support students as we move forward. Thoughtful planning and the realization that it’s not “business as usual” will help not only students, but also departments looking to recruit, retain, and serve physics and astronomy graduates in the postpandemic world.

A version of this article appeared in Physics Today Online https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.5.20211102a/full/

References

1. S. Nicholson and P. J. Mulvey, Roster of Physics Departments with Enrollment and Degree Data, 2019 (College Park, MD: American Institute of Physics, September 2020), https://www.aip.org/statistics/reports/roster-physics-2019.

2. American Institute of Physics, Percent of Physics Bachelor’s Conferred to Women, https://www.aip.org/statistics/data-graphics/percent-physics-bachelors-c....

3. American Institute of Physics, The Proportion of Physics Bachelor’s Degrees Awarded to African Americans and Hispanic Americans, https://www.aip.org/statistics/data-graphics/proportion-physics-bachelor....

4. “Interactive: The Looming Enrollment Cliff,” Higher Ed Magazine, CUPA-HR, Fall 2019, https://www.cupahr.org/issue/dept/interactive-enrollment-cliff/.

5. D. Barrett, “Fall’s Enrollment Decline Now Has a Final Tally. Here’s What’s Behind It,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Dec. 17, 2020, https://www.chronicle.com/article/falls-enrollment-decline-now-has-a-fin....

6. E. Hoover, “The Real Covid-19 Enrollment Crisis: Fewer Low-Income Students Went Straight to College,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Dec. 10, 2020, https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/academe-today/2020-12-10.

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Impact of COVID-19 on the Careers of Women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2021), https://doi.org/10.17226/26061.

8. All reported differences between groups are significant at p < 0.05.

9. TEAM-UP Task Force, The Time Is Now: Systemic Changes to Increase African Americans with Bachelor’s Degrees in Physics and Astronomy (College Park, MD: American Institute of Physics, 2020), https://www.aip.org/diversity-initiatives/team-up-task-force.

10. Employment and Careers in Physics, April 2020, https://www.aip.org/statistics/reports/employment-and-careers-physics.