Where Are the Physics Jobs? Ask the Statistical Research Center

Spring

2017

Connecting Worlds

Where Are the Physics Jobs? Ask the Statistical Research Center

Rachel Kaufman, Contributing Writer

There’s a wide world out there for those who hold a physics bachelor’s degree, and the Statistical Research Center (SRC) at the American Institute of Physics is shouting that from the rooftops.

While the allure of academia and research is compelling, students who make physics the focus of their undergraduate years have a wide range of opportunities open to them—as Sigma Pi Sigma members undoubtedly know.

The Statistical Research Center compiles data on “all things physics and astronomy,” senior survey scientist Patrick Mulvey says. A recent publication reports on physics bachelor’s who graduated in the classes of 2013 and 2014 describing where they went after graduation. That report was released late last year.1

In that report as well as a second report focusing on sectors of employment, salaries and job satisfaction, SRC researchers Mulvey and Jack Pold noticed a few standout highlights:

- Most undergraduates who immediately enter the workforce are employed in fields other than physics and report high levels of job satisfaction.

- Physics undergraduates who enter the military have the highest job satisfaction.

- Bachelor’s degree recipients who attend a research-heavy school are more likely to continue to graduate school.

Why might these be true? Radiations spoke to Mulvey to find out.

1. Most undergraduates who immediately enter the workforce are employed in fields other than physics and report levels of high job satisfaction.

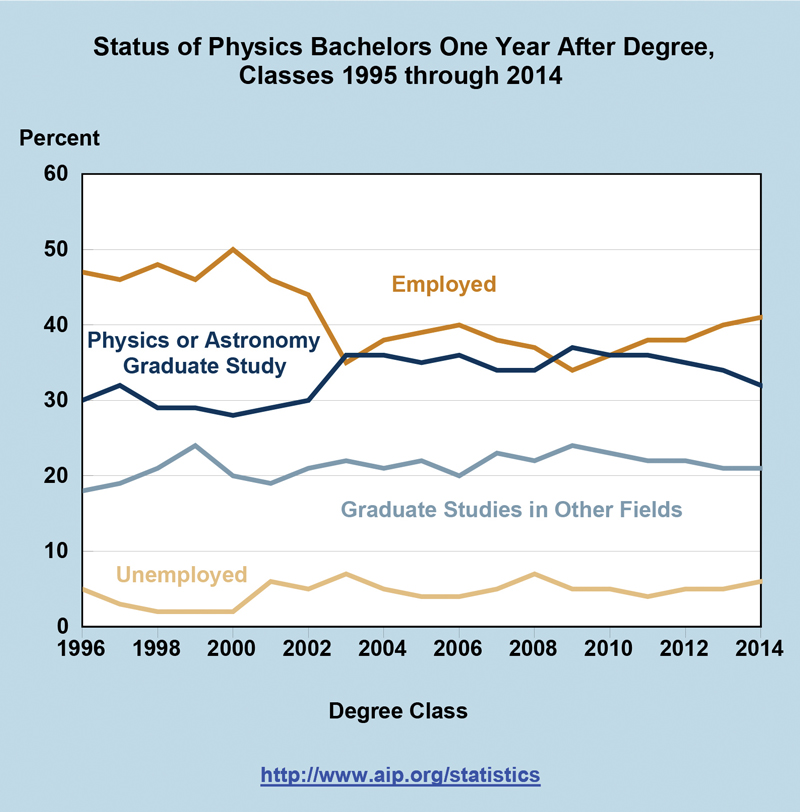

In the most recent survey, a majority of bachelor’s (54 percent) went on to grad school and 41 percent were working. The proportion of bachelor’s going straight into the workforce has increased over the last five years with fewer going into physics or astronomy graduate studies. (The proportion who went to grad school for other subjects has stayed mostly the same.)

Of the 41 percent working, most were working in the private sector (65%), mostly in some sort of STEM field, but not necessarily physics. In fact, only 5 percent of those employed in the private sector said they were working in the field of physics.

But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, Mulvey says. That’s just the reality of the working world. “The larger companies in the private sector who would hire a physicist—let’s say 3M. They’re going to hire the physics bachelor’s for their skills in problem solving, for being a quick learner, for being a bright individual, having good programming skills, and put them to work there. The people doing the higher level physics, that level of work … is going to be done by a PhD physicist….A physics bachelor would not be hired to lead a research project.” But their problem-solving skills and general knowledge background qualify them perfectly for engineering and computer science jobs, which together make up 59 percent of the jobs physics bachelor’s accept in the private sector.

These bachelor’s degree holders are, by and large, happy with their jobs. Overall, more than 80 percent reported being satisfied with their work.

Of the bachelor’s degree holders in the private sector, a quarter of them said they were working in non-STEM fields. They were less satisfied with their jobs, but still, just over half reported being satisfied overall, and about three-fourths were satisfied with their job security. Even in non-STEM fields, physics bachelor’s find their skills are appreciated. “[Physics] is thought to be a difficult subject and someone who succeeds in it—and it’s probably true—can probably succeed in many things,” Mulvey says.

And then there are the teachers. Many high school teachers don’t think of themselves as working in STEM, even if they’re teaching a STEM subject, but almost all physics bachelor’s teaching in high schools were teaching STEM, according to the SRC’s report. High-school teachers reported high levels of satisfaction with job security and level of responsibility. Overall, 75 percent of high school teachers were satisfied with their positions. Teachers often reported that working with children and helping them understand physics was among the most rewarding aspects of their jobs.

2. Physics undergraduates who enter the military have the highest job satisfaction.

Only about 6 percent of physics bachelor’s entered active-duty military after graduation. (The data excludes graduates of the US Military Academy, the US Air Force Academy, and the US Naval Academy, as those graduates are on a specific career path unlike that of others who enter the military after graduation.) But those six percent were overwhelmingly satisfied with their jobs, with almost all citing high levels of job security, responsibility, and opportunities for advancement as reasons. “They’re respected, and they are doing physics, and they are really involved in what they’re working on,” Mulvey says. “They’ve got a lot of responsibility.”

3. Bachelor’s who attend a research-heavy school are more likely to continue to graduate school in physics.

According to the report, students who study physics at a research-intensive university are more likely to stay in physics for graduate study. It may seem obvious, but a finding of the SRC’s surveys is that students who attend schools where graduate programs are offered are more likely to go to graduate school. “Is it that the environment…encourages students to go on to study physics because it’s the culture around them, or is it the student that chose that type of environment?” asks Mulvey. “It’s probably a little of both.”

What does it all mean?

Without data, scientists and policymakers can’t make good decisions. That’s why all the research SRC conducts on behalf of AIP—not just on bachelors’ career choices, but also on masters’ and PhDs’, women and minorities, faculty trends, teaching conditions at high schools, and so much more—is available for free online.2 (SRC also puts its data-crunching employees to work to do surveys for other groups; that data is often released on a case-by-case basis, depending on the client.)

In short, the SRC’s mission is not to influence or affect policies and programs, but simply to provide good data. The SRC has twelve permanent staff members who together can provide a “beginning-to-end” service—from questionnaire design to statistical number-crunching to writing reports.

In the case of the “one year after graduation” survey, we already know, anecdotally, that only a small minority of physics majors go into tenure-track academia and that we should prepare students for possible careers outside that track. But, says Mulvey, “I don’t want [that] to be anecdotal. I want it to be evidence-based.”

What does it mean that, even after 30 years of compiling similar reports, some are still surprised that so many career options exist outside of the ivory tower?

“That the dissemination of these findings is not as good as I would like,” he says.

1. Physics bachelor’s 2013 and 2014

2. Research SRC conducts on behalf of AIP